-

Posts

1,472 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Forums

Events

Downloads

Gallery

Mods

News

Store

Posts posted by temnix

-

-

While doing the usual "sanity check" for GLOBbing SPL files, I was thrown off by an SPL called CDDETECT.SPL. It's not a real spell, it has no abilities or global effects. Its size, therefore, is exactly 112 bytes, so it should have been bypassed by SOURCE_SIZE > 112. In fact, though, it kept bucking the installation until I added an exception for it. That nipped it, but I don't want to patch things blindly, to be surprised by any other pseudospells that might happen in some installation. There is another SPL that I routinely exclude by name, by the way, in case a mod is installed on Icewind Dale: #BONECIR. I don't remember if the problem there is the same as here or not. But I would like to know why this 112-byte stops the SOURCE_SIZE > 112 check?

-

Most likely, this version involved a test script which existed in my override folder but which I did not include in the distribution. +files are test devices. That part has been dropped now, and the archive updated.

-

Good enough. I was going to make a fix myself, but this spares me the labor. I'm including this file in the first post.

-

No, I don't have it yet. Thanks.

-

For some reason this area's TIS in Near Infinity won't be extracted as a PNG on neither my older nor my newer computer, where I have Shadows of Amn installed. If this is a problem on my side nonetheless, I'll give credit to anyone who provides the PNG.

-

My website storage is permanent, more or less. I just accidentally trashed the file.

-

The download link here was not working. It is now.

-

As I'm practically evaporated from these boards, it doesn't get me anything to champion any views, but it's still not true that if CGI is "normal to them," it's normal as such. It will be fake even if no one recognizes that it's fake, just as the world could live without any painters who know natural forms, and still the shapes would remain as they would have been perceived by those with the eye to see. And what the young people lack to understand the difference is simply education. Knowing nothing except Photoshop is not an argument.

-

I'd rather read de las Casas' "Shortest Account of the Destruction of the Indies." It's going to have a lot of detail, it's from life, and I might improve my Spanish. And the reason I went to it is because I'm playing "Colonization."

-

I can say this for CGI, computer effects really can bring to the screen something that couldn't be in any other way. I don't mean anything small, handheld or lifelike. A doll wolf doesn't necessarily look more convincing than a computer wolf, it may even always be a little ridiculous, but the computer wolf is not like the real thing either. Even if the CGI people copy the animal from photographs to make a still form, it shows itself false the moment it moves. But when it comes to scenes with masses of objects already artificial, identical elements or things that simply don't exist in reality (rays, projections, appearing screens and so on), there is no substitute. In the 2nd season of "Lexx," in the last episode, there are enormous battles between Mantrid drones and 790 drones, where thousands of these mechanical arms fly at each other and battle. They are all simple CGI creations and don't pretend to be anything else, but they give viewer's consent enough footholds. There is no way something like that could be done with practical effects, even though the model for the drones shown close and handled by the characters is a real arm from plastic and polyurethane foam. This is not the purpose for which CGI is used today, however. Instead of complementing reality, they replace it.

Speaking of wolves, using real animals is another part of "effects" that seems forgotten today. In "Wolf," the 1992 or 1994 movie with Jack Nicholson, there is a scene with a number of them advancing on the hero and one of them even pretending to bite him. Then they run away. Obviously some animal handlers were involved. Why not use more of that instead of a fake wolf? Because a fake wolf is cheaper, because all the good animal handlers have probably retired, because there would too much red tape to clear before bringing on set animals - who are probably endangered, too... Yada yada, the typical "make it cheaper make it faster" shit. I'm not really as flabbergasted at this as I was when I started the topic, though. I wish I was. But I understand now that the viewer who would scoff at today's CGI, like myself, is also a dying breed. Today's young audience doesn't care about realism, because it grew up on computer games, and for many other reasons. After all, everything else around is fake too, from food to politicians. They are all poured of the same virtual metaplastic.

-

In fulfillment of the Make Amends Make Haste initiative announced across the Imperial Democracy last year, the Townhall and the Planning Authority introduce Reburied Past, Refurbished Future – an ambitious project to expand the social conscience area. As the President-Chancellor Mutate has promised, all private residences will be invited to an opportunity to host a cadaver from our tragic past as it is remodeled into a promise for the future. Tax incentives so far undisclosed will be extended to all participants in this permanent program and certain construction regulations waived to speed up its implementation. “We start gently. Potentially, though, we expect every resident in our town to host a cadaver,” said the Mayor in his regular Bathrobe Address. “Putting one in your lawn is a powerful symbol of reckoning with a difficult past in this phase of our multination’s history. SGEEP, that is, Standard Ground Engagement Examination Process, will be adjusted and some phases dropped to make this possible. The Plank of Architecture is 100% for it, the environmental impact reviews are all in, and what some people quoted as the maggot concerns will, in fact, improve soil fertility. We will all appreciate that in kindaspring when the cadavers sprout young green palms all over town. I think that’s a beautiful forward-looking symbol.”

~ The Morning Zoomerang

Introduction

SpoilerNIMBY Stiff is a game of allodial angst and mercurial integrity. The players represent the owners of private residences alarmed about a looming development project. The project is a cadaver the town administration wants to lay out over their land, offering tax incentives. These increase all the time, and the residents’ defiance frays. The cadaver is turning out to have more and more surprising properties than stated upfront, however, "discovered" (invented) by the players themselves. Every player needs to decide what to do: accept the cadaver when its incentives become lucrative enough and drop out with a lesser, Yes In My Backyard (YIMBY), victory or dig in and outlast all the others. The sole remaining player achieves the greater victory – Not In My Backyard (NIMBY).

Any number of people can play, so long as they arrange themselves in a circle, star or another figure such that each sits between two others, one to the left and one to the right, and faces a third. These three other players are considered one's neighbors. When the seating is irregular or the group very large and there are no players directly across, the third neighbor can be chosen by throwing a paper wad at someone in that direction. As players exit with lesser victories or become eliminated, those who remain close ranks. If an across neighbor is out, the player to his left substitutes. A free space should be left at the center, called ground zero or pit or hole. This were bets go in the beginning of the game, if it is played for money. The passport with all cadaver properties is also kept there.

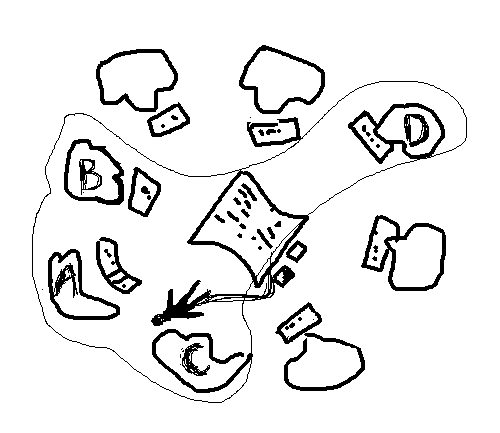

An eight-player game:

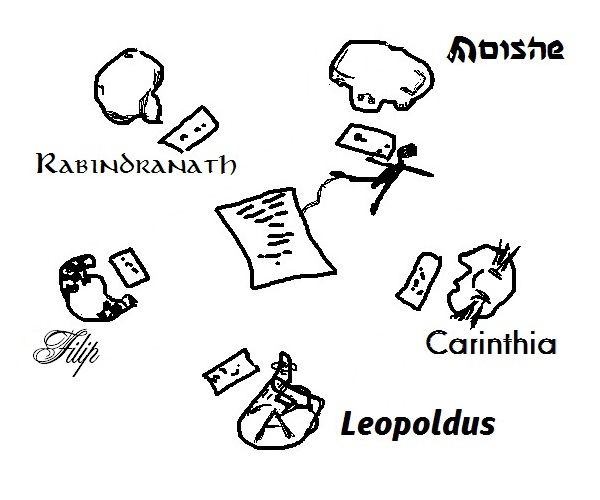

A five-player game:

Betting

SpoilerThe game can be played for live money to give players more of an incentive to seek a YIMBY victory. The bets put forward by the players, whether in equal amounts or not, as they decide beforehand, are divided in two (the sum of currency should be even). One half of the money in the hole is reserved for YIMBY victories. The first player to take the YIMBY road out takes half of this sum – one fourth of the entire bank. The next player to drop out as a YIMBY takes one half of the remaining YIMBY money, i.e. one eighth of the bank, and so on, with every next YIMBY player getting less and less. The last player to stay in the game rakes in the intact NIMBY half and any remaining money in the YIMBY section.

Order of play

SpoilerThe game consists of two stages: exposition and melee. In exposition the players' starting situations are determined by a combination of lottery and a sort of blind Dutch auction (explained in more detail below). The melee stage is the actual play, and it begins with the cadaver in one of the player's plots. The player considers whether to accept the cadaver for the incentives currently posted by the Planning Authority, which begin at 1 galactic credit at the end of the first turn and double every turn thereafter. For a YIMBY victory the incentives must be twice or more the player's estate value, a statistic discovered after exposition. At the beginning of the first turn there are yet no incentives on the cadaver. Whenever a player cannot have or does not want to accept the cadaver, he shoves it over the fence to one of his neighbors along with an emerging fact about this prize – a property he comes up with.

These properties can be positive or negative, apply briefly or for the rest of the game. The property is recorded in a note, kept face down at ground zero for two turns, at which time it will be flipped up, read and its effects apply. The upside of the note, visible to all, carries a brief description, which can be metaphorical, loose or intentionally misleading, although this is grounds for a dispute (see "Contesting notes"). It is almost completely up to the author of the note what rules and effects he can (try to) introduce. The cadaver may be Marxist, hobo-hosting, wind turbine, sewage-inadequate, investor-attracting, anti-Semitic, memetic, titanic, silver, noisy, traffic-increasing, for local businesses, radioactive, equal opportunity, fracking, neck-kneeling, woke, affordable, historical, ugly, expensive, crime-reducing, vaccine-mandated, partisan, pornographic, pedophile, injection-site, alt-right, Renaissance Fair, open-air, indigenous, roomy, 5G... Offense can be an important tool in manipulating and confusing the other players. As the cadaver tumbles over to a neighbor’s, other players may try to steal it for themselves, while the incentives continue to accrue and tempt. The next turn begins.

Which of the two victory paths will be more relevant and attractive is going to depend completely on the players, their strategies and interactions, and perhaps on butterflies flapping their wings over an ocean. Other than the starting sum of 1 galactic credit for incentives, the game does not use any concrete values for statistics, which are all worked out between the players. For the estate value lottery the starting conditions are written on anonymous notes, which are then drawn at random. It is possible for the group to toss about millions and billions of galactic credits, if those are the numbers someone risks submitting to the pot, in which case the YIMBY path to victory will be a remote possibility.

Statistics

SpoilerThere are four statistics each player needs to keep track of and update: estate value, acreage, current stress and stress ceiling. The players record these values and their changes on the sheets in front of them, viewable by all. The stress ceiling never changes.

Estate value is individual and determined by a drawing of lots. Acreage is a common value and arrived at through bidding. Once both are known, the players can move any number of points between these statistics for a starting combination they prefer, but in the game's main, melee stage they have to trade with neighbors to buy one and sell the other. A player whose estate value or acreage descend to nil is eliminated. Players with high estate values stand the best chance of outlasting others around the table, yet it may be advantageous for YIMBY-aiming players to keep a low estate value. Ample acreage is necessary to keep down current stress (simply "stress" for brevity), which always begins at nil but may increase after certain actions. If it reaches the stress ceiling, a common value also determined through bidding at the start of the game, the player goes insane, kills his neighbor with the highest estate value (the across neighbor in a tie) and commits suicide. Both players are eliminated.

Trading with neighbors

SpoilerEvery turn a player is allowed to carry out one trade with each of his neighbors. The neighbor must agree to deal. The player may increase his estate value at the expense of some acreage, in the process the player's stress increases by the same amount. The opposite operation, selling estate value for acreage, reduces stress by the number of acreage points gained. Neighbors are entitled to setting their own terms. Stress changes on both sides are always equal to the amount of acreage lost or gained, but otherwise neighbors are not obliged to exchange estate value and acreage at the one-to-one rate or in the amounts offered. No trade may be so big as to deprive either party of all estate value or acreage or raise stress to the ceiling. Purchase of such acreage as would reduce stress below nil is permitted, but stress is still only reduced to nil.

The original, independent distribution of points between estate value and acreage does not change stress.

Exposition. Lottery and bidding

Spoiler1. Every player writes an estate value number and drops the note face-down into ground zero. The tallest and oldest player is chosen to shuffle and deal the notes, clockwise and ending with himself. The players put the notes, still face down, next to themselves.

2. Starting from the player across from the dealer and going clockwise, the players propose a stress ceiling. The lowest value called is adopted.

3. Starting from the player across from the caller and going clockwise, the players propose standard acreage. Again, the lowest value called is adopted. The players then turn their notes with estate value face up. They can immediately convert any amount of estate value for acreage and vice versa – the only time in the game this can be done without trading with neighbors.

Melee. Phases of a turn

Spoiler1. Protocol: the cadaver arrives at a player. The whistleblow note from two turns ago is flipped face up. Debates and votes on the meaning of the note are held. If the note is uncontested or its original text stands after the vote, it comes into force. Its effects and description are copied onto the cadaver's passport. The cadaver's accumulated effects apply in reverse order (starting from the latest). The right neighbor of the author of last turn's note folds it, without looking on the bottom side, to show half of the contents.

2. YIMBY: the player with the cadaver considers a YIMBY victory, if the incentives are twice or more his estate value. On a YIMBY exit the cadaver passes on to the left neighbor, the incentives remain unchanged and the next turn begins. The cadaver may be stolen as usual (see below).

3. Agenda: if a YIMBY victory is impossible or not wanted, the player writes a whistleblow note (or uses one prepared in advance) with an emerging property of the cadaver. The note will come into force two turns later. The following limitations apply:

a) Whatever its other prescriptions, the note must alter the estate value, stress or acreage of a player or players once and instantly, at a delay, for every turn until the end of this game or for some definite number of turns;

b) It must not refer or target a specific player or a definite estate value, stress or acreage, although it can quote amounts higher than or lower than a certain number, nor may it move the stress ceiling or touch upon the incentives of the cadaver in any way;

c) It may not dictate a change of statistics such as will instantly eliminate any player (by raising stress to or above the ceiling, setting estate value or acreage to or below nil), although it can dictate a change of these statistics that may lead to elimination even the next turn after the note is read, unless some action is taken. However, the written adjustments in no event can exceed the highest estate value or acreage currently in the game or half of the stress ceiling value. If greater, they are reduced accordingly. All fractions are rounded down;

d) The note must also include a stress price. If the note is contested on account of some alleged violation, the players can all vote on any number of alternative readings. The interpretation with the highest number of votes is accepted, with the player currently in possession of the cadaver enjoying two votes (from support of the Authority). The note stands on a tie. A defeated interpretation costs this much stress to the player who advanced it, including the writer of the note, if he was challenged and lost the vote. The stress price must be lower than the stress ceiling;

e) The effects may not preclude the players from any of the actions allowed under the rules, such as trading with neighbors, stealing the cadaver, turning up notes etc.

On the reverse of the note the player writes an adjective or another short description of the nature of the effects. The description does not have to be accurate and may, in fact, be made equivocal or misleading. In practice, however, the less relevant a description to the contents of the note, the more likely it is to be contested. As the note is being prepared and before the description is shown, the other players may trade estate value and acreage with their neighbors. (Even if the player uses a ready note, the others must be allowed reasonable time for these trades.)

4. Rumor: the player makes trades himself before showing the description of the note.

5. NIMBY: the player adds the description to the passport, moves the cadaver to one of his neighbors and the whistleblow note to ground zero. The note may not be touched until the next turn, when it will be folded to display half of the contents. If a note is turned up accidentally during these two turns, it is discarded; if this happens still during the turn when the note was made, its author prepares a new note. No extra trades are allowed. Also at any moment during the two turns any player may turn up a note intentionally and pay half the stress price, rounded down. The player may do this in the knowledge of the stress price on the second turn, if the folded note happens to display this number (but only if the price would not take him to the stress ceiling), or take a blind risk, in which case it is possible to reach the stress ceiling from the discovery, fly berserk and be eliminated along with the neighbor across. No trades or underwriting are allowed for turning up notes, players must pay their own stress. Turning up a note for stress does not cause it to come into force earlier. The note is set to the side until it triggers in due course. The author of a note is permitted to declare his intent to submit it face up, if he desires the contents to be known from the beginning, and do so, but turning it up later would cost him stress the same as the others.

6. Honeydew: the cadaver's incentives double.

7. Campaign: any player other than the sender and the addressee may steal the cadaver in transfer. This is done by bidding any number of points of stress short of reaching the stress ceiling. If no one tops the bid, the stealing player gains that much stress and becomes the one to receive the cadaver on the next turn. Other players are allowed to join the bidding, including the addressee, but not the sender. A participating player may make one trade with each of his neighbors to exchange real estate for acreage and thus lower his stress, but only after making a bid. If the bid would take the player into the stress ceiling, stress points from the neighbors work as underwriting by them. The winning bid must be paid, however, even if it results in the player's insanity and elimination (along with that of the across neighbor). The cadaver then passes to the left neighbor of the vanished bidder. The next turn begins.

Contesting notes

SpoilerThere is no exhaustive list of reasons for which a note may be contested. Any reason is an excuse, and any excuse can be a reason if it is convincing or useful enough. For instance, ambiguity of phrasing is only a problem if the other players don’t like the effects of the note. Then they might extend the excuse of vagueness to the others, inviting them to jump on this chance to vote down the text, or become upset and agitated themselves – or pretend to be upset and agitated, or engage in doublethink and sort of really become that. Outrage works well. Any of this is likely to happen only when it is advantageous to the player, although some people might be as idealistic as protest notes on actual flaws. In practice even what seems like a clear violation of the basic rules, expressly forbidden, may be allowed through if no one objects. The part that makes the difference is the vote and having enough support to defend a text or replace it.

Against conspiracies

SpoilerThe players may not communicate explicitly over game decisions and strategies or pass any notes to each other. There are no special punishments for those who violate this rule or use a code or sign language developed before, but such behavior is likely to create trouble for them from the others when votes on notes are counted or quid-pro-quos considered.

Example game. Exposition

SpoilerFive people have come together for what is likely to be a fast and furious game; games with more players take longer and allow more leisurely and elaborate strategies. Leopoldus (A), Filip (B), Rabindranath (C), Moishe (D) and Carinthia (E) have arranged themselves in a loose garland so that everyone has someone more or less in front and to the sides. The cadaver, yet without properties, lies between them.

The players all write a note with an estate value for someone to establish the scale of the game. They could discuss this in front and arrive at some kind of consensus, but this would put at a disadvantage Filip and Rabindranath, both of whom want a free hand with their turns. Filip likes taking risks and thinks he can kick the others out of the competition with big changes, ending it in a few turns, so he wants to write a relatively small number and certainly does not care for the others to know his method. Rabindranath's plan is to last just a few turns until the incentives on the cadaver get into the double figures and accept it for a YIMBY victory. For this his own real estate value should be low. The plan could not work, of course, if it was known to the rest of the players, and Rabindranath's grandfather has been shot by Maoists-Taoists, so to his mind the idea of setting a common scale smacks of a downshifted Communism. Besides, somebody is going to end up with the cadaver, and how is cooperation going to address that fact of life? For all these reasons he plans on a low number as well, with a small buffer for security. As it happens, though, his idea of a low number is 120, and Filip's is 10.

Among the others Leopoldus believes absolutely in his good luck and gambling wit. He reasons that whatever the others give him, he can make the best of, but for his part he can start on the road to YIMBY even so early on by screwing over one of the players. He does not want to make a ridiculous note with 1, but 5 is going to be a nasty surprise for someone... YIMBY is Leopoldus’ aim, because he is kind of short of time just now.

Carinthia is in for the long haul. She enjoys the game process, the hairdresser's appointment is still hours away, and she is curious about the properties the others make up for the cadaver. Small numbers annoy her, and she writes 1,300 on the note.

Moishe puts 1 million on his. "Hopefully I'll draw that one," he thinks, "and if it's somebody else, G-d bless him! I always was a Wagner fan, even if he hated us kikes."

The notes are stacked at ground zero. It does not matter who shuffles the notes and deals them, but the men telepathically agree a girl would look hot at that operation, and someone delegates Carinthia. She obliges. The notes slide along the table, but they players may not look at them yet. The player to Carinthia's left will get to propose a stress ceiling now. Leopoldus occupies that place, and he thinks of stress as a weapon, not as a danger, and would like a nice abstract stockpile of it for his use. At the same time, going too high will just end up in a flop. What will the others think reasonable that he still can use? He shrugs and proposes 150. Filip sits next. His thoughts run more or less along the same lines, but to be original he wiggles his eyebrows and intones "149."

To his left Rabindranath tries to figure out what figure would help him in his plan to accept the cadaver quickly. He would have liked a higher ceiling, in fact, so he could steal the cadaver from anyone when the time was right, but now he begins to think of a backup plan – make the others burn themselves up with excess stress spending while he sits calmly on the sidelines. They may tug that cadaver back and forth, his own estate value, he is certain, will be low enough to snatch the prize the first time the thing comes along. "Let's lower the ceiling on them, hah," he thinks and says "50." Other faces turn a little glum. This number still does not mean much, any player can always get rid of stress by trading for acreage, but everybody will have to be careful now. The cadaver will have to be made useful for stress relief, hmm! Moishe has no opinion on this, so he maintains 50, and Carinthia, the last, regretfully affirms it. She would not want anyone to go berserk and kill her, but if the two of them do it to each other, it might be entertaining...

The standing figure for the stress ceiling has been proposed first by Rabindranath, so it is Carinthia on her bean bag chair across from him who must start on acreage. She thinks she has set the scale of the game with her estate value submission of 1,300, whether for herself or another, so it seems logical to her to keep acreage in the same range. The two numbers should be convertible into each other with comfort, she thinks. But the depression of the stress ceiling by Rabindranath has soured her somewhat on the others. "Hmm, that one is planning something, for sure," she is thinking. "And I don't know about the others. Why can't they just play and enjoy themselves? Schemers! The lowest number declared wins, and they are just bound to bring down anything I start with. So let's go high. Not crazy high, but – 5,000." Which is what she says. Leopoldus has also felt a squeeze in the last round of bidding, especially given the tiny scale he had tried to give the game for estate value. Now he wants to have at least abundant acreage, or there will be no flexibility at all. He lowers the proposal to what, he hopes, the others will support – 1,000.

Rabindranath is beginning to feel himself the party pooper. If he crushes this bid like the last, the others are bound to hate him. "That's what being under a glass dome is like," he mutters to himself. "No one's said anything, and yet they are all against me. Equalize! That's how Communism spreads. Well, I'm bound to give them an inch, or they'll take a mile out of my hide with cadaver fallout." He lowers the proposal to 500. The others have no reason to object, and Rabindranath's acreage stands. The player across from him, Moishe, will be the first to play, but first they all must find out what their estate value is, and if they are unhappy, borrow from acreage or add to it. Some quicker, some slower, they turn over the notes next to them.

Filip opens an accurate, notepad-born origami of periwinkle and his eyes bulge at the figure of 1,000,000. Moishe has even signed the note, for some reason. What is Filip to do with this? On one hand, this kind of wealth makes him invulnerable pretty much to everything the others will dare to hang on, that is, discover in the cadaver, because its properties may not target particular players. On the other hand, now he is public enemy number one and only, and everyone around the table will rack their brains to take away this advantage, so obviously unjust because they don't share in it. "I can see it in their eyes," he thinks. "Sure, if they don't invent something clever, I'm gonna outlast them all a thousand times. Why the hell did Moishe go so high? Well, maybe he thought we'd all write something huge... Man, I gotta get to know the people I play with better!" To bring his two main statistics into better synch, he channels half of the value into acreage.

Carinthia sees 120 on her note and is disappointed that others did not support her idea of a well-paced game punctuated by spectacular adventures. "Someone is in for a quickie, for sure," she ponders. "But we'll see." She turns 300 of her acreage into estate value.

Leopoldus grits his teeth when his own 5 stares back at him. "Don't panic, Leo!" he tells himself quickly. "What do I have now? The ceiling is pretty bad, but I've got some acreage. I should turn a lot of it into estate value now, because if I do it during the game, that'll increase stress. The important thing is to keep any effects that lower estate value from happening. And work out some kind of deal with one of these two jerks, in case I absolutely need estate value... Wait, wait. I'm forgetting! So focused on NIMBY, I forgot the other road to winning. Keep the estate value low! I have the best shot at a YIMBY victory now. If I only leave a point of estate value now, the cadaver only has to be worth 2 galactic credits when it comes my way in two turns: Moishe's, then Carinthia. It's a huge risk, but I'll take the cadaver and win this game right away. They'll try to stop me, for sure, but I'll contest any note like crazy. That's what the stress will pay for. Give me my two turns, and the cadaver goes in my backyard!" He keeps a single point of estate value.

Rabindranath draws 1,300 and waits to see what Leopoldus will get. Noticing a 5 there, he decides to give up on his original plan. "I can't beat that," he thinks. "Sure, I could swap almost all of this estate value for acreage, but Leopoldus here still gets to turn first. I don't dare risk staying with such a low estate value, who knows what might happen... But I'll cut up Leopoldus, I will! He thinks he'll just wait for three turns and the cadaver will land right into his lap. If I sat closer to Moishe, or if I got Carinthia to go first and skip Leo... Oh, he'd just lower his estate even more to be ready on the second turn. He is bold like that. I wish I was so bold... A nice ass on him, too... Well, I'll stop him anyway. I'll steal that cadaver on the way if it's the last thing I do." He has no definite plans for what is to happen after that, so he decides to prepare for a drawn-out competition and converts 300 estate value into acreage.

Moishe looks at the 10 given to him and sighs. "What can I do with this?" he reflects. "I'm making the first turn, so I can't accept the cadaver, even if I swap these scraps for acreage. Maybe on the second round, when it comes back this way... as I hope it will... the incentives will have swollen up to a couple of hundred by then... my estate value will be low enough, for sure. And they will all be fighting against Leopoldus the first few turns. That gives Filip a break. The cadaver will be getting nicer and nicer meanwhile... Can't sit on this ten, though, until then. One of the effects is bound to drop people's estate value, and when that happens, I'm out. No, the YIMBY choice is too risky. I need a cushion." So surmising, he turns half of the acreage into estate value.

The final statistics of the players before melee:

Leopoldus: estate value 1, acreage 504

Filip: estate value 500,000, acreage 500,500

Rabindranath: estate value 1,000, acreage 800

Moishe: estate value 260, acreage 250

Carinthia: estate value 420, acreage 200

Everyone's stress is at nil. The stress ceiling is 50.

Moishe begins his turn.

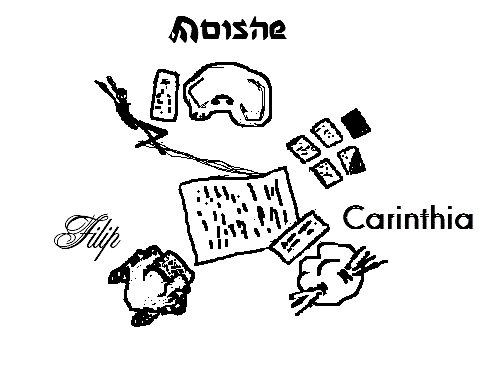

Example game. Melee. Turn 1

SpoilerMoishe proceeds with his strategy of waiting out the others. He would rather they be eliminated than leave with YIMBY cash, so to negate what has to be Leopoldus' design he draws up a cadaver note that says "All players' estate value increases by 10," then considers what would be an incontestable description. He writes "hydrant-repainted" on the back of the note and pushes the cadaver over to his neighbor on the left, the same player whose turn to play it will be – Carinthia. To keep the others from contesting the note Moishe puts the highest possible stress price on it, 49. Then he ends his turn. The cadaver's incentives are now at 1.

Carinthia reads the description on the note and knows, more or less, what to expect. She folds the note, but, against Moishe's hope, the stress price is not on the revealed half to spook all of the others. Leopoldus is worrying Carinthia as well. To be on the safe side, she decides to bypass him and send the hydrant-repainted cadaver over to her across neighbor – Rabindranath. His high estate value means that he is not likely to seek a YIMBY victory any time soon. She is not without a nasty streak, however, and decides to screw with the players on that side of the table as well. Rabindranath and especially his neighbor Filip have too much estate value. How about a social leveling surprise? She writes "heavily-taxed" on the top side of the note and on the reverse the following: "The highest estate value is made equal to the next-highest every turn." That sounds nice and vaguely just. The meaning is also nice and clear, and she thinks she could get the votes in support, if push came to shove. To prevent any quibbling from the two "gentry" players, she writes 49 as the stress price. Then she ends her turn. The cadaver's incentives increase to 2.

The first conflict takes place. The cadaver would go to Rabindranath, but Leopoldus bridles at being bypassed. Moishe's note he can contest, but he must have the cadaver – now! His confidence in his ability to outbluff the others is infinite. He declares that he steals the cadaver for 49 stress. Now, who is going to top that, break the ceiling and lose the game? Unfortunately for Leopoldus, this confrontation was predictable from a mile away, and the others quickly rally. Filip does not want the cadaver on his immense estate with that "heavily-taxed" tag, although waiting on this occasion might cost him the game. He thinks the others will do something, though, and Rabindranath, in fact, cuts in. He wants the cadaver just so he can throw the present over the fence to Filip's on his turn. He bets 50 stress and turns to his left neighbor, Moishe, for a trade: 50 acreage for 50 estate value. He can afford these numbers, and the trade would leave Rabindranath's stress at nil.

As expected, Moishe declines to give quite so much, because for him this exchange would mean a 50-point increase in his own stress, a game-over. But he understands that Leopoldus must be stopped and knows that, beside himself, Rabindranath can only make trades with his other two neighbors – Filip, who may or may not help, and Leopoldus, an enemy at this junction. And why should Rabindranath have such an easy time with this cadaver theft? There is also the fact that Rabindranath is gay, and Moishe quietly dislikes faggots. All this leads Moishe to turn to Carinthia to spread the risks. Moishe asks her, and she agrees, to buy 20 estate value from him. This expands his acreage by the same amount and redeems 20 points of the stress – all Moishe wants to take on for Rabindranath. Hopefully Filip will be good for the other 30 stress Rabindranath wants to bid for the cadaver with, or the guy can invest his own stress, indeed!

Filip still does not know quite what to do with all the estate value and acreage that have been thrust upon him. He had thought of himself as a ballsy and fast attacker, like Leopoldus, but chance put him a position where his interests are in long-term, slow play. Now the "heavily-taxed" property coming up worries him much more than taking on a little stress, although the ceiling is as near for him as for the others. This is his only vulnerability. When Rabindranath turns to him with a request to sell 30 estate value, he agrees to provide 10. Rabindranath now has a 30-stress reduction backed up by his neighbors and grudgingly adds 20 of his own. Leopoldus looks around, but the neighbors won't sell him anything at this point, of course, and his estate value is already at 1. He could not swap any for acreage, even if the others were open to dealing with him. Leopoldus cannot match Rabindranath's bid of 50 stress and withdraws from the competition over the cadaver.

The current statistics of the players are:

Leopoldus: estate value 1, acreage 504. Stress nil.

Filip: estate value 500,510, acreage 499,490. Stress 10.

Rabindranath: estate value 1,030, acreage 770. Stress 20.

Moishe: estate value 240, acreage 270. Stress nil.

Carinthia: estate value 440, acreage 180. Stress 20.

Turn 2

SpoilerThe cadaver is waiting in Rabindranath's backyard. Before everything else, the "hydrant-repainted" note is flipped up and comes into force as a permanent property. Everyone's estate value goes up 10 points.

Leopoldus: estate value 11, acreage 504. Stress nil.

Filip: estate value 500,520, acreage 499,490. Stress 10.

Rabindranath: estate value 1,040, acreage 770. Stress 20.

Moishe: estate value 250, acreage 270. Stress nil.

Carinthia: estate value 450, acreage 180. Stress 20.

The YIMBY ambitions of Leopoldus have been thwarted, but only for the moment. It will not be long before the hydrant-repainted cadaver's incentives grow to twice his estate value, which is the lowest on the table. Leopoldus is only concerned about getting the hydrant-repainted cadaver, a bit later... To protect himself a little from surprises (what does "heavily-taxed" mean?), he trades 20 acreage for estate value from Carinthia. She sees no harm in this now, and it eliminates the stress she took on while banding against Leopoldus. To her mind, he has been disarmed by the time being, the hydrant-repainted cadaver is far away, and the alliance with the others was only temporary. His willing acquisition of estate value must mean he wants to play like the others, with higher numbers there. It does not occur to her that Leopoldus can never play in the same style because of his very different starting conditions. Leopoldus puts on a nice face, swearing black revenge on the others in his heart.

The others are more concerned about what Rabindranath is going to do with the hydrant-repainted cadaver. The meaning of "heavily-taxed" interests everyone, and they would not mind an early look, but the folded note, now on its second turn, is flashing a menacing stress price. Still, there a lot of expectation that someone is going to risk contesting it next turn. Probably the richer players. Will it be Rabindranath, who is hosting the hydrant-repainted cadaver now, or Filip with even more to lose? Rabindranath himself has no doubt that the note will shatter somebody's estate value, but how will it work? Will it be an one-time event or some new rule? Who will be the target? He recalls that the main, fixed rules forbid referring to any specific player... If there is going to be a general change, he will gain nothing by dumping the hydrant-repainted cadaver over Filip's fence. But the main problem on his mind is devising a winning strategy. All these back-and-forth exchanges and rallies against outlaws like Leopoldus are well and good, but what does he need to do to eliminate the others? Keep bringing down their estate value, he decides. This will make YIMBY invitations sing their siren song to the smaller players, and he will only have Filip to contend with on the NIMBY path.

In the end Rabindranath prepares a note that says: "All players' estate value decreases by 100 every turn." Muttering "Devil's advocate!", he calls this "planned-economy," jots 49 as the stress price and will push the note to ground zero. First, though, he asks Filip to sell him some acreage to reduce stress, but Filip likes to keep this low himself and declines. He asks for the same from her neighbor across, Carinthia, who also refuses, because stress is a more obvious weakness of the two richer players. In something like desperation Rabindranath turns to the last source, Moishe, who displays sudden business acumen: he will sell 20 acreage, but for the price of 90 estate value. Rabindranath resigns to this but chucks the hydrant-repainted cadaver over to Moishe's to lure him on the first chance to drop out when the tax thing hits next turn. The players' statistics are:

Leopoldus: estate value 31, acreage 484. Stress 20.Filip: estate value 500,520, acreage 499,490. Stress 10.

Rabindranath: estate value 950, acreage 790. Stress nil.

Moishe: estate value 340, acreage 270. Stress 20.

Carinthia: estate value 450, acreage 180. Stress 20.

The hydrant-repainted cadaver's incentives increase to 4.Turn 3

SpoilerThe hydrant-repainted cadaver at Moishe's becomes heavily-taxed. The contents of the note are read and Filip's immense advantage evaporates on the spot. He would really like to contest the note on the grounds such as... why is only one player taxed, for example? But he is rather sure that the others want him brought down this big peg, whatever their differences. His great wealth is simply too inconvenient for them. And if the vote goes against him, gaining 49 stress on top of his current 10 will be the end. So he says nothing and glumly submits to the logic of leveling down.

Leopoldus: estate value 31, acreage 484. Stress 20.Filip: estate value 950, acreage 499,490. Stress 10.

Rabindranath: estate value 950, acreage 790. Stress nil.

Moishe: estate value 340, acreage 270. Stress 20.

Carinthia: estate value 450, acreage 180. Stress 20.

Filip allows himself a little chuckle: Carinthia did not think to cover acreage in her rule, which means he can still sell some of that and bring his estate value up again, though the stress ceiling would stop him from going too high there. The annoying part is that Carinthia's rule is permanent, and it will cut his estate value again the next turn and forever. Filip resolves to introduce a different note with an opposite effect, favoring big estate value. He will contest the coming "planned-economy" from Rabindranath, and probably get help from others, because that will probably be too strenuous for them.

Moishe looks at his notepad. "They know that I know that they know that I know that they know that I can get away with anything on a Holocaust note, and nobody will dare to speak up against it. But are any of us smart enough to follow that to the end? Hopefully they also recognize that I have standards. Let's see what I can do now... A storm of contesting is coming up, and Carinthia will want to get rid of her stress. Let her do the arguing. I can redeem her stress at a profit and just sit back for a while as this note floats along..." He wants to make a note entitled "psychoanalyzed" and reading "All players' stress decreases by 10," but sticks out his tongue and adds "...but 3 turns later increases by 30." He dubs this "CBT-treated." He puts the stress price at 1, not minding if the others find out sooner.

As the note is being written, Filip prepares for a contest. He invites either Rabindranath or Leopoldus to take some of his real estate, even at a double rate. Not that Filip needs acreage, but he wants no stress restricting him in any challenges ahead. Rabindranath refuses: even a simple sale, let alone an acquisition of a double amount of estate value, would be cut off and nullified by the taxation Carinthia has introduced right next turn. He sees how Leopoldus would jump at the opportunity, however, because he then would stand a better chance of a YIMBY victory again. Rabindranath is unaware that Leopoldus has decided to play it a little slower and wait for the incentives to grow a bit, but he is the only one who knows what "planned-economy" is going to mean on the next turn, nor is anyone else eager to take on any stress and turn that note up prematurely. The others are gearing up for a dispute. Leopoldus makes a simple transaction with Filip – sells him 10 acreage for 10 real estate.

Moishe finishes the note. Before slipping it into the hole, he offers Carinthia a trade: take 20 acreage from him, resetting stress, but give him 50 estate. She hesitates, but he offers her the hydrant-repainted, heavily-taxed cadaver to do with as she pleases. She agrees but thinks this will be the last time she lowers estate value so. Moishe throws the prize over without worrying that anyone might try to steal it. The incentives have yet to look serious even for Leopoldus' minimum.

Leopoldus: estate value 41, acreage 474. Stress 30.Filip: estate value 940, acreage 499,500. Stress nil.

Rabindranath: estate value 950, acreage 790. Stress nil.

Moishe: estate value 390, acreage 250. Stress 40.

Carinthia: estate value 400, acreage 200. Stress nil.

The incentives on the hydrant-repainted, heavily-taxed cadaver equal 8.

Turn 4

SpoilerThe "planned-economy" property from Rabindranath is revealed and would apply. Everybody's estate value would now drop by 100 and continue to drop every turn, but Filip objects. Had he not, Carinthia would, and if not her, Leopoldus. The first two players do not want to lose so much of their estate value and hope to outlast the others, but Leopoldus' motivation is exactly opposite. He remembers that the basic rules prohibit notes that cause anyone's elimination on the same turn they come into effect, so his estate value would drop only to 1 now. On the next turn, however, the deduction would expel him from the game.

Filip needs to make a case against the note, offer an alternative interpretation, and then a vote will be held. The loser will pay the stress price. Filip, Carinthia and Rabindranath have prepared by disposing of all stress. Leopoldus is worse off, but he would still call for a vote, as it is a life-and-death situation for him. Moishe just observes. "It's, like, misleading language!" declares Filip. "I don't think "planned-economy" can mean we all lose estate value. More like, it would be a redistribution of value." This is, in fact, the inverse of what he believes, but it is enough to vote on. Filip's proposal is that the player with the highest estate value distribute up to 100 points of this statistic between players other than himself, any way he chooses, every turn. That player is likely to be Filip himself, since he still has any amount of acreage he could swap. Unsurprisingly, this interpretation fails, as everyone votes against it. 49 stress is lobbed at Filip like so much rotten fruit.

Now another rival of Rabindranath's has to make a different suggestion, otherwise the original reading will stand. Carinthia does not care to endure the same kind of backlash, so she proposes a compromise: "Every turn every player donates as much estate value as he likes into a special reserve. This starts from the player who has the smallest estate value. In the end, 100 estate value must be collected. The remaining points short of 100 are all donated by the player with the most estate value. The reserve is then divided between all players equally, fractions rounded down." This proposal is a jab at Filip and Rabindranath, the two richer players, but inadvertently it messes with the YIMBY resolve of Leopoldus, who does not care at all to receive these freebie estate value points turn after turn. His own estate value is not so high as to contribute much, which means the others will be keeping him in the game exactly when he wants to leave it on a lesser victory! "Screw this charity!" says Leopoldus out loud and votes against the proposal. Filip and Rabindranath support him in the opposition, but Carinthia has two votes because of the Authority behind her.

Now it is up to Moishe to decide how this vote will go. Ties are wins. If he votes against this reading, Carinthia will not only take on 49 stress but become his enemy. He will then have two options: either let Rabindranath's reading stand, in which case he will himself be eliminated in a few turns along with Carinthia and Leopoldus and leave the whole of bet money to the winner of the Rabindranath-Filip duel, or propose his own version. He has nothing ready in mind, however, and the angry Carinthia will, no doubt, vote against it unless she is sure his idea will save her – and perhaps even then (who can tell what a woman will do?). If Moishe supports her reading, Leopoldus will lose, break the stress ceiling and fly out of the game, but that changes nothing much for Moishe. He does not know Leopoldus intimately to regret this either. His careless stress-reducing-but-then-boosting note, on the other hand, is something to attend to, it may be dangerous even to himself. Moishe votes in Carinthia's favor, her reading stands, Leopoldus' is defeated.

30 + 49 = 79 stress: Leopoldus is eliminated.

Moishe also kept in mind, while the others somehow neglected, that another player would go out with the crazed Leopoldus – the neighbor with the highest estate value. Filip on the left from Leopoldus had 940, Carinthia on the right 400, Rabindranath 950. A short axe murderer scene is permitted to play in everyone's mind, and Rabindranath is also finished. Had the players besides Moishe remembered the inevitability of somebody else's demise, they might have voted differently from the start.

The cadaver is now hydrant-repainted, heavily-taxed, planned-economy in the Carinthia-suggested sense. The new property applies. The remaining players are gathering 100 estate value. Moishe gives 20, Carinthia 40, Filip the remaining 40. It is all the same to him, because the next rule to apply will be: "The highest estate value is made equal to the next-highest every turn." After the "planned-economy" redistribution the statistics become:

Filip: estate value 933, acreage 499,500. Stress 49.Moishe: estate value 403, acreage 250. Stress 40.

Carinthia: estate value 353, acreage 200. Stress nil.

The "heavily-taxed" property applies:

Filip: estate value 403, acreage 499,500. Stress 49.Moishe: estate value 403, acreage 250. Stress 40.

Carinthia: estate value 353, acreage 200. Stress nil.

The players move closer to fill the gap left by Leopoldus and Rabindranath. With just three participants left, everybody is now a neighbor to the others. Next turn the meaning of the note "CBT-treated" will be revealed, the players' considerable stress will be lowered but send them scrambling for solutions down the line. Estate value will have to be sold, no doubt, to Carinthia, who can demand just about any ratio from the others, but even she will have to think how to deal with the stress. Though in possession of the hydrant-repainted, heavily-taxed, planned-economy cadaver, she is not considering a stress-lowering note at the moment, because she has always thought CBT a good, solid approach to psychological problems. Therefore, Moishe could not have implied any negatives. His note must simply be for reducing stress, nothing more. His first note was all-positive, after all.Relieved that this is taken care of, Carinthia switches to selfish villain mode and considers whether she may not produce a note that would bump up the others' stress a little. The stress ceiling cannot be moved, the rules forbid it, but current stress can. If she could just knock the others into the abyss in two turns... But she has enough foresight to understand that they will contest any such note from her. Two votes against one, the only way to push through her proposal would be to have the hydrant-repainted, heavily-taxed, planned-economy (soon to be CBT-treated) cadaver in time. Then she could benefit from a veto, supportive of interpretations by default. But she must send it over now, and later those two will just be tossing it to each other.

What is she to do? Carinthia will try to drive a wedge between Filip and Moishe, who end up in an unwilling alliance, brothers in stress. She will speculate on the sole importance difference in their situations – Filip's huge remaining acreage. Now is her chance to write a note that will benefit Filip and convince him that she is his ally against Moishe. She is worried about Moishe rather more than about Filip. She considers writing a note that will say "Any player may swap 100 000 acreage for 10 fewer stress, in increments, and in the end take on 15 stress." This could property could be called, eh, "gardens of Hemiramis" from that book she read. Was it Hemiramis or Demiramis? Anyway, it will be mysterious enough, and if she bends over like this in this blouse and shows some cleavage, the guys will probably stay short-circuited until the note comes up. Filip should snatch up this opportunity. He'll pay for it a little stress, and that will be enough to knock off Moishe!

Carinthia also remembers that she has one trick left the others would be too afraid to use: stealing the cadaver. For the next couple of turns she can command more stress than both of them combined. The note is prepared and dispatched. Carinthia passes the hydrant-repainted, heavily-taxed, planned-economy cadaver to Moishe to keep him pacified. The incentives rise to 16. The next turn begins, and the game continues…

Questions to consider

Spoiler- Should Carinthia try to bump off Moishe, given that his murder-suicide would also eliminate Filip across and that both of them are keenly aware of this danger?

- At what number of players does the game become unwinnable? Three? Two?

- Is it more rational for the players to agree to reduce stress and award a lesser victory to someone or begin scheming again as soon as their situation improves?

- Can more be expected from a player than to act on the basis of his ability, information and view of the world?

- Why shouldn't have Moishe indulged in his homophobia against Rabindranath, even knowing this for a bias, if that delight was a source of satisfaction for him not covered by the rules? What if there had been another homophobe at the table and they formed an effective alliance of tastes?

- Should players be outraged at others' suggestions, given that they know the recipe for outrage and can cook some up themselves? Will they all the same?

- What cup size in Carinthia's cleavage matches the performance of a sound strategy? Isn't it a sound strategy already?

- Is there a rule that forbids a change of rules? Can that rule be changed? If not, can *that* one?

- Would there be a strategic or tactical difference if the players competed against an inhuman and implacable force rather than each other? Would such a struggle still count as a game? If the rules were codified, abstracted and copyrighted against alteration, would that recreate the situation of an inhuman and implacable adversary?

- Is a sufficient and adequate, let alone complete, description of a situation even possible? If it is not possible, what is gained by proclaiming that it is possible – and by whom? Would this game be better with personalities and considerations omitted? Who would it be better for?

- Who, or what, is it that wants the game to be mathematically describable?

- At what point does the game become too complicated to disentangle? May it then be easier won by a) pushing through with a definite strategy or character; b) savagery towards other players; c) invention of new rules the player can better own?

- Should a bonus be given to players who defy the inertial tendencies of gameplay, or should they be punished as disruptive mavericks? Can this be voted on? Do they get a vote? Does support of the Authority give extra votes? What is the ultimate purpose of the game – enjoy the process of playing or proceed to winning to take away the money, if any?

- If a common scale of statistics was agreed on beforehand, what is the sense in which that would make playing easier? Who would be more interested in this kind of ease?

-

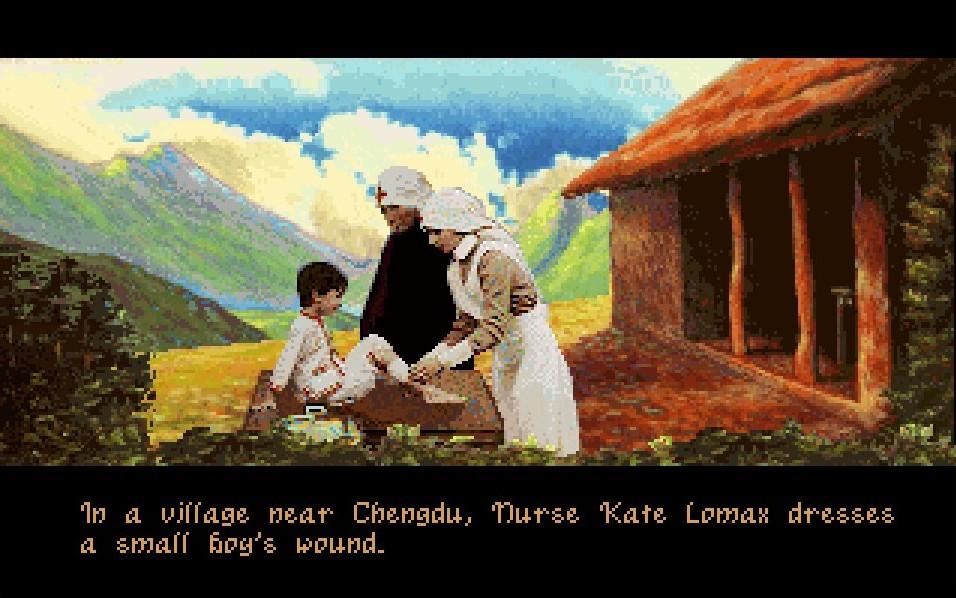

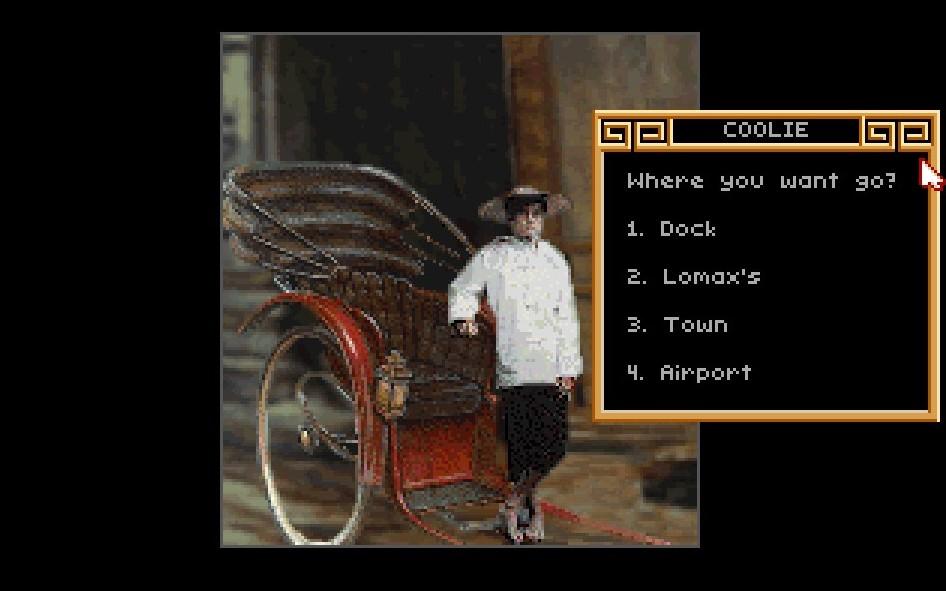

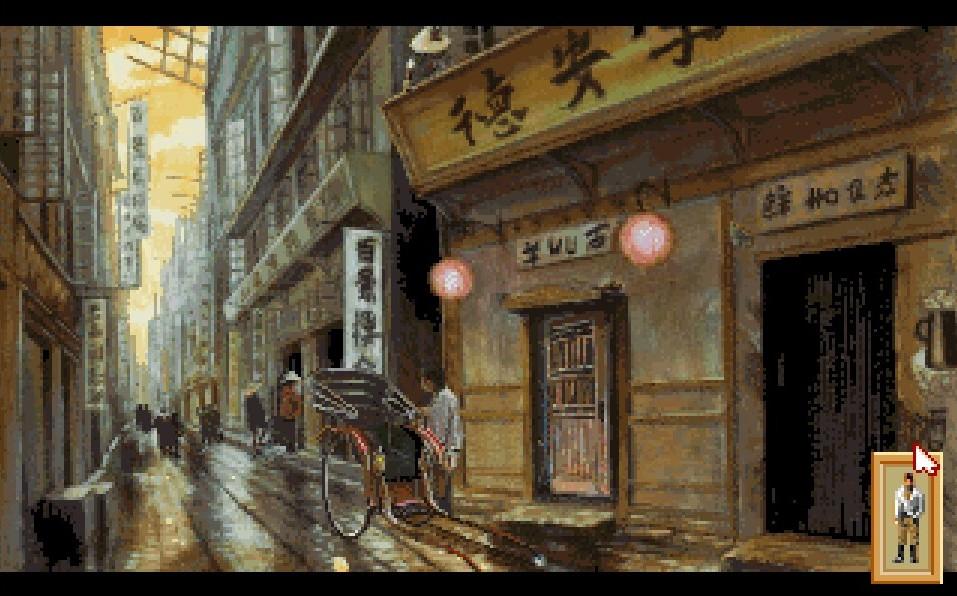

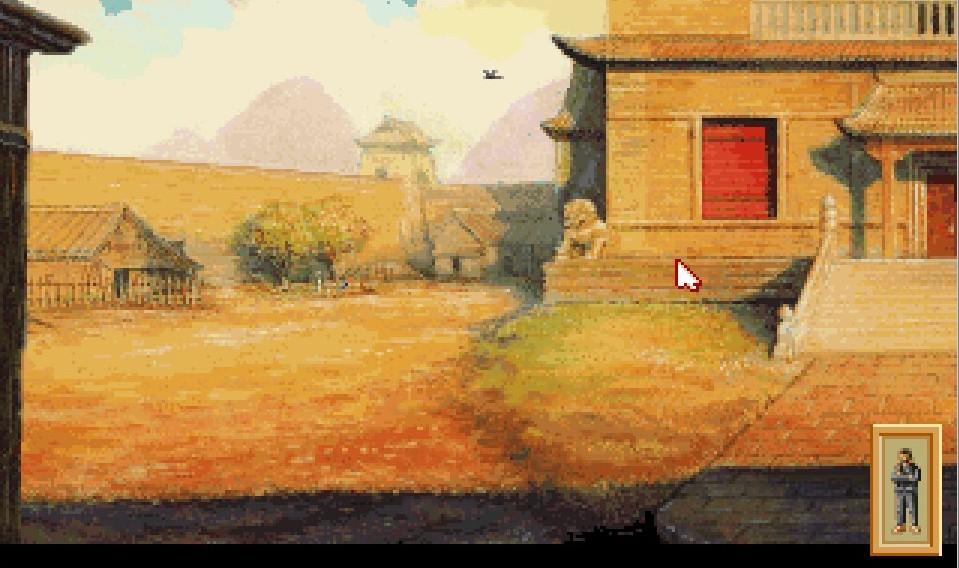

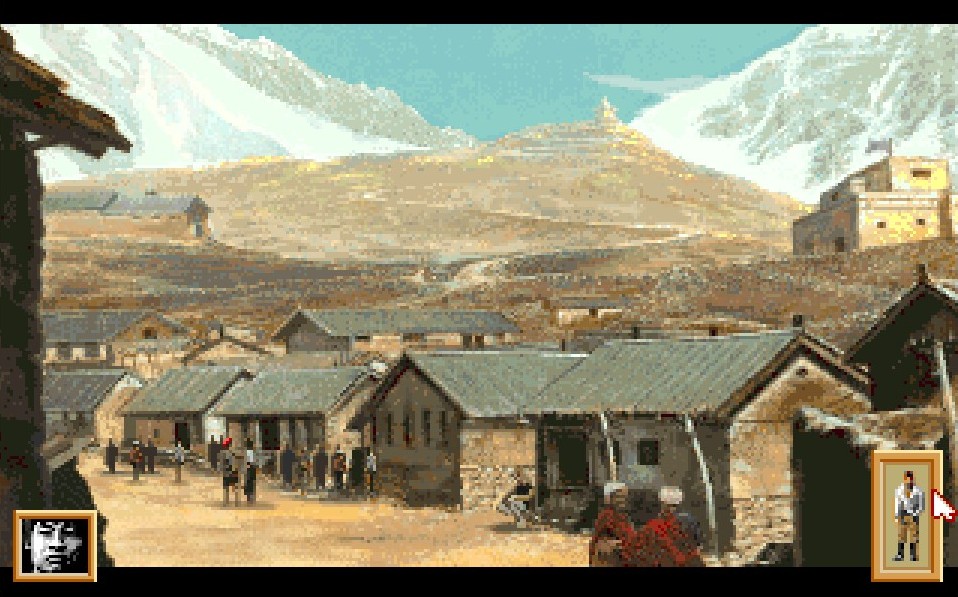

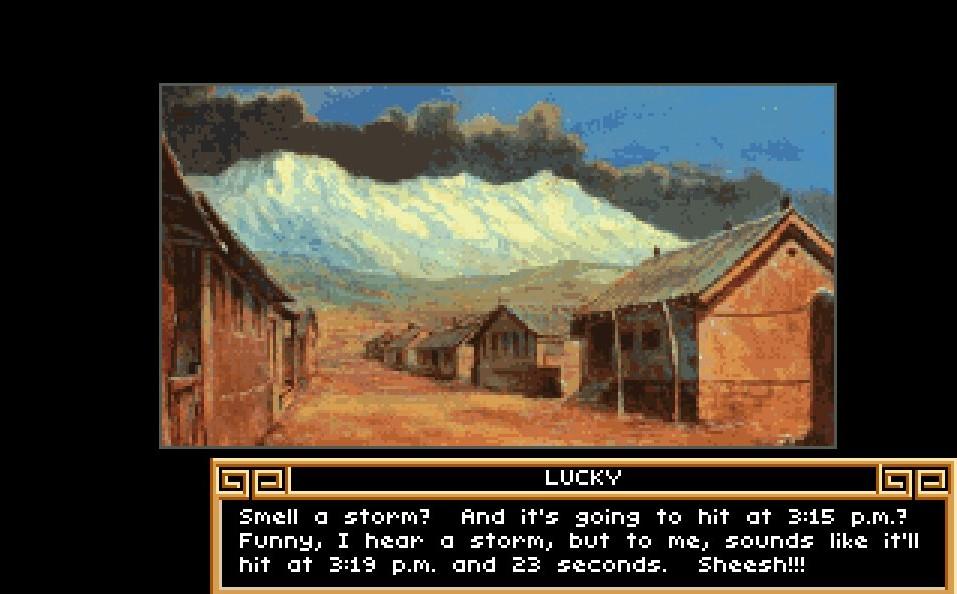

I was looking through an old games website in search of something to play, and I came across an adventure by a Sierra company, Dinamix, called "Heart of China." The screenshots I glanced at were attractive and the review did not mention any special difficulties aside from some arcade sequences, which, as it would turn out, I could even skip. So I thought, this should be nice and simple enough. Point-and-click. I had done that. And that is how the game turned out to be, an adventure with a context-sensitive cursor for picking up items, combining them in the inventory, applying them outside, talking to people in a menu - all of the invisible defaults for adventure games. I did not appreciate or notice the game's release year - 1991, all of those quests with familiar controls would be made a good five years later. This one's manual actually had to explain that the game is not controlled via a parser. So there was a lot of striking innovation there, in fact, but that is not what made an impact on me, nor the game's loose plot, which only just begins in China, certainly nor the dialogues that get weaker and cornier by the minute. Because of all that I gave up before very long, but all that is irrelevant. What blasted into me were the game screens, the backgrounds against which the action unfolded. They were drawn by hand, like in many other games before tiling and 3D came along... Baldur's Gate uses tiling in places with identical tress, by the way... but those screens were drawn, and how! The skill was unbelievable, the immersion, even ethnographic detail complete! Some of the images look so true, so correct that I had to wonder if they weren't copied from some photographs of, say, Tibet circa the beginning of the 20th century, but they couldn't have been. Not likely.

To repeat, I have played adventures and Sierra adventures, I have seen nice backgrounds, original backgrounds, apt backgrounds. A lot of cartooney backgrounds, ranging from nicely unusual to predictably simplified. The sort of scenery I remember from "King's Quest" or "Quest for Glory" doesn't require that much skill, although by today's standards it may impress. And I wrote about "The Blade of Destiny" on this board not long ago, though that is neither a Sierra game nor an adventure. Still, it's adequate. Lots of games were adequate. Some kind of dude with a sword, looking more or less convincing against a tower. But there is still a long gap between that level and what I saw in this game, which just took me aback. My eyes were blinded with the light from the painted skies, the shades of scattered miscellanea, animated bystanders talking and nodding their heads were absolutely transporting. I ended up saving screenshots with an external program so I could look at those pictures later, but I find it incredible that artists of this caliber could be available in dozens - yes, that's about how many are listed in the credits here - to work on nothing more than a videogame. We are not talking about a Frank Frazetta alone in the world here. Apparently people who could paint such things - they had to paint these pieces, how else? - were in plentiful supply. Apparently this was the level you could order from industry professionals, because I don't think that these people burned out and slit their wrists after submitting these screens. They probably got paid, bought a little vacation for the family, then sat down to make another thing, no worse. This boggles the mind, because I can't think of any game today, whether AAA or AAAAAAAAA, that could feature this kind of true mastery. Compared to this, modern games that get praised for their "execution" are done by cube-shaped fingerless daltonics.

Sometimes the designers used living people for models, there is a lot of embedded photography of actors there, but mostly for cutscenes or close-ups. This accounts for some of the finesse, but only for some. The actors are made to blend so well with the background that usually there is no telling who has been captured and who - drawn. There are some less convincing exceptions in a few places, but the impression is still tremendous.

On the first picture the scarf is animated and waving in the wind, by the way - not an easy detail to draw.

Oh wait, the last one doesn't fit.

-

@InThePineways Well said, only the disconnection is not just from the source stories but from the culture and mindset that made them, or something like them, believable and relevant. Until only a few decades ago the majority of people, in all parts of the world, were brought up in societies that believed in the supernatural. They had common creeds, whether Christian, Muslim, Hinduist or any other. I'm actually from a country with several generations of atheists, the Soviet Union, that is, and that gives me something of a detached perspective, but it's still true that until recently ideas like the existence of magic, mysterious worlds adjacent to the one humans inhabit and so nature spirits and shapeshifters, life after death and therefore ghosts, and so on were in the realm of possibility, even if social life in the spotlight was already industrialized and bureaucratized. But now those subjects have evaporated from the thoughts of nearly everyone. Zealots aside (and they are not a healthy counterexample), who doesn't think nowadays that consciousness is in the brain and that when the brain dies, it's all over? Who doesn't think that science falls flat on its face every now and then but is, all the same, the only real kind of knowledge? Who doesn't accept the evolutionary story of the past, devoid of events other than the big meteorite that killed the dinosaurs? And human history is about this corrupt king waging war on that one, no better; guns, microbes and steel. That's a far cry from giving Britons an origin in the ancient Troy or the idea of a manifest destiny. All of those fanciful imaginings have been laughed out of court, and even the words are gone off tongues. I think the word "werewolf" is more or less undecipherable by an average brain today - the idea behind it is too strange. Is it a dog? Is it a man in a shaggy suit? Hollywood and pop culture still reuse the tropes, but look at ghost movies there are so many of: they are completely about jump scares and ugly, distorted visuals now. I don't know a single one that honestly takes up a hypothesis that there is some continuity of consciousness after the death of the body, a parallel continuum to the events the eye can see. Such a model would instantly appear too outrageous even to the makers. It's the same with everything else that used to have a dangerous edge as a representative of a vast, unknown world outside.

And there is no influx of fresh notions for the cauldron of the imagination. Science fiction may get a boost when the social order changes and priorities become realigned, but I don't see poetry and fantasy coming back as essential social forces. That would require a return to a preindustrial or a turn towards a non-industrial society. Castaneda writes at one point that the interests and methods of modern shamans are different from those of their ancient predecessors because they have no social function. You will never a shaman as a village healer or a court magician, he notes. Well, what is the point, then? Without relevance, how can fantasy be interesting or vital?

That was in response to you. I was talking about something else in my post, though - growing out of the books and movies that used to fascinate and inspire. Other people have had a worse time at that, I'm sure. I've never been a fan of R. Salvatore, so I've never had to contemplate seppuku upon discovering what trash the Drizzt books are. I don't think I actually did grow out of what I still respect, however. Not out of the original Dragonlance books, not of the first Moonshaes trilogy by Douglas Niles for the Forgotten Realms. Not out of the wonderful Aladdin animated series for TV, a jewel of the 90s. Not out of the better parts of Xena, Hercules, Conan with Schwarzenegger (I prefer the second movie), and I keep "Red Sonja" on my hard drive. They are still powerful, as are the comics from the 70s issues of Heavy Metal. And Magic: The Gathering for many years held the flag high. But they really don't make them that way anymore. The external world does not correspond to these essentially simple stories and visions. It surges around them violently and wants to tear one away. As I look at so many wonderful MtG cards, I feel myself lapsing into a sort of reverie that is perfectly natural and would be congenial to, say, Thoreau and other Transcendentalist writers in the United States or their Romantic counterparts in Europe. I want to stay in that frame, in that mood and in that measure of time. I don't want to change, or become smarter, or soak up worldly experience outside. I'm not interested in splaying my being in synch with the undulations of this (im)material civilization and reality that I find out of those little windows or my own window. The coronavirus may kill me, but it will never excite me. Yet, unlike the Transcendentalists and Romantics, I realize that there can be no development to the stories. Two hundred years ago it would be different. When those writers and painters walked in the wild, or semi-wild (strange enough for the inhuman character to be felt but not so rough as to kill them), the artists and other, congenial spirits still had a future ahead, a possible future, in that environment. It was still possible, debatable, for the world not to trundle on in the direction it then did. They could, at that time, still develop and enjoy divergent notions. And maybe in nature and in open sensitive spirits there would be enough response and echo to maintain a place and a time where the poet and the painter's sentiments would be relevant and verdant. There could be a separate community through time.

But that's not where we are now. It is impossible to continue traditions or countercultures once started today. Take Wicca. Its origin story was always laughable, but it was true, serious and cool in its intent and statement - a different mode of relating to the natural world and intuition. That went on until, oh, the 90s. But what does it mean to be a Wiccan now? Or a goth? I keep seeing young people in black, but what does that stand for? They have their faces buried in smartphones the same as the squares. I'm not even talking about commercialization and commodification, though, I'm saying that there is no future in dreams. To a dream sent there is no dream answering. Even if a global revolution singes this world order off the planet, something even more technical and rational and proletarian will, no doubt, take over. It is not logically necessary that this should be so, but I can't avoid this conclusion, knowing what I do about human nature.

-

Truly, I have no idea what you are talking about. But I made all of the later mods especially take into account EET string numbers.

-

Just because you are so persistent: I'm through with modding. Nothing is going to happen.

-

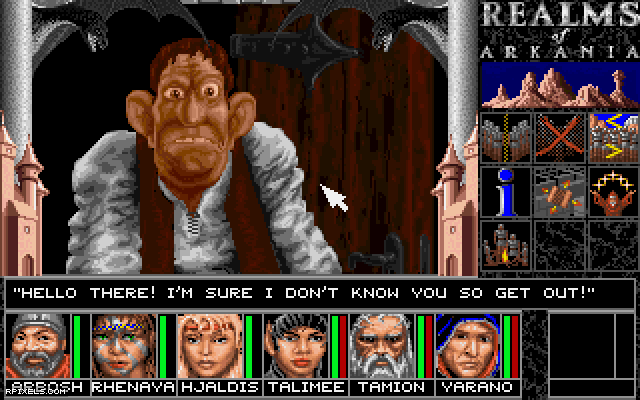

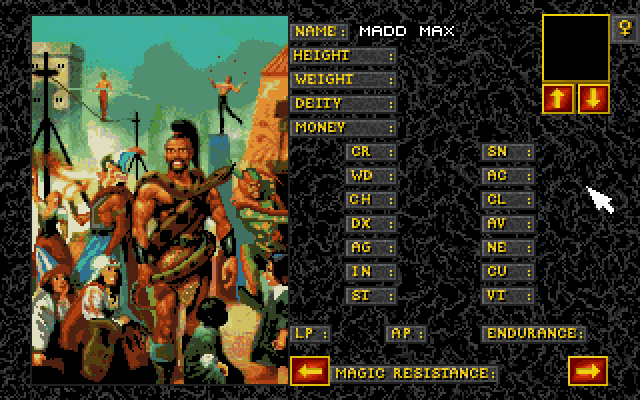

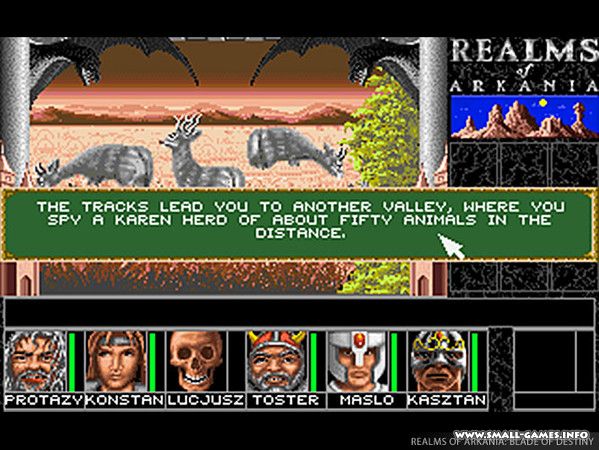

I recently came back to, played and finished Realms of Arkania: Blade of Destiny, the first part of a role-playing trilogy set in the world of the Dark Eye system from Germany. This game came out in the United States in 1993, translated and published by Sir-Tech. "Blade of Destiny" was followed by "Star Trail" and "Shadows of Riva" a few years later, and the sequels are said to have improved many aspects of the first part. "Blade of Destiny" was also remade in 2013 for a modern engine, and a bunch of other Dark Eye games came out thereabouts, some rather well-known. I haven't played them much or at all and don't intend to, but this information provides a little background for what follows. Some screenshots will also give an idea about this first game. What follows, then, is not a review or a Let's Play or a comparison between the original and sequels but an observation on the features of the game, including those that are unsatisfactory or hands-down broken, which add up to a very different experience from what is considered good and sensible today. The underlying principles are different. This is not instantly obvious as one plays, for some time the absence of this or the presence of that can be chuckled off as a rustic quaintness - because since then videogames have rolled on the highway to progress, don't we know that? Eventually, though, I realized that this road aims for another place and that the goalposts of which modern developers are so proud don't appear here for a reason... mostly. The broken parts sometimes contribute to this difference, and the whole thing is a portrait of a great sincerity. Obviously without thinking much, without drafts or backup plans in many places, the 25 year-old T-shirt-wearing Germans from the 90s take the player through what Roger Zelazny has called an "opening" experience, whereas modern games and their reviewers measure success by how air-tight they can make a "closing" experience. And I believe that a road that "opens" is the right one for art, to which category game-making belongs and mod-making can belong.

Volumes have been written about the essence of art, and all attempts and explanations can, of course, be subverted, profaned and mocked, especially if there is a buck to be made from that. But at its core art is a personal effort at expression that admits no reproduction but by its personal nature becomes personal to the audience. So far from being irrelevant to others, true art, whether great or small in its achievement, is the ultimate relevant, viscerally linking creation. This game, for its part, is a sort of diamond in the rough where the roughness, as far as I'm concerned, is more important than the shiny stuff, which is just carbon. Now, most people come for mods to games like Baldur's Gate only to look for tweaks to a gameplay that they already enjoy, nothing more novel than that, and they can be excused (what else is one to do with them?). But in a mod or in a whole new game, a creator would do well to appreciate the asymmetrical and disturbing principles that reveal themselves in play here, and probably in many other old games, though "Blade" is particularly unpolished. Without a conscious intention not to do but only to do something else this game breaks every rule worked out since that guarantees people a smooth, predictable, repeatable, reportable, youtubeable time. Instead they are thrown about and see some kind of light. Like any real work of art, "Blade" can't be enjoyed twice - not really; it has no replay value, even though many elements are random here. Beside frustrating combat and other features not to be endured again, there is simply no point in going through it a second time after one has got it, but that single time through leaves an indelible impression. It is interesting to compare this game to Baldur's Gate with its immense replayability, and as I have spent so much time modding BG (I recently deleted more than 19 Gb's worth of crash dump files alone), I am in a good position to see every point where they diverge. Therefore I can derive lessons from this difference and make recommendations: do such and such, thou modder, if you want to support expectations, but such and such if you mean to break new ground.

In the following I allow myself to emphasize the essential differences that "Blade" exemplifies with boldface. Combat should be shown, just to get rid of it, but it is the worst and flattest part of the game, except that by the end my wizard advanced enough to turn orcs such as these into toadstools. Spells have Latin or pseudo-Latin names, aiming for effect, but without any translation into English or description in the interface - or even the manual.

A few words about the plot and what the gameplay consist of. Orcs are mobilizing to march on Thorwal, the capital of northerners in this region of the world. Their army will be ready in a year. The hetman (ruler) advertises for adventurers to find the magic sword of the hero Hyggelik, hidden somewhere in the wild a couple of centuries before, and slay the orc chieftain in a symbolic duel, which should break the alliance of tribes. The party is told the name of a distant descendant of Hyggelik's, living in a distant town, to start the search. Upon their visit the man gives them a piece of a map that should show the location of the sword and a couple of names of others who may know something of that old story. Traveling from village to village, from town to town, by foot and by boat, on the overland map, the party collects more scraps, usually just by talking to the contacts, though they need to do a couple of quests as well. Between and about the populated points dungeons, road inns and encounters are scattered.

There is a lot about this game that doesn't deserve to be discussed here. It doesn't matter what the character classes are like or how balanced, the races are rather ordinary Tolkien fantasy stock. The indoor art is often irrelevant, and the temples in this Norse land all look like something out of "The Clash of Titans." The music is lovely, but, as I said, this is not a review. Someone who decides to play the game will find plenty of information online about automapping or the interface, and lots of warnings and hints. To begin about the relevant differences somewhere, the towns and villages are not planned to the player's convenience. They are not radiated as an urban architect would line them, nor arranged in lanes or districts. They are chaotic, but not from a random number generator. All of the houses are equally small, but they are often clumped in irregular groups. The rest varies. Cities have blind alleys in places or a stretch of impassable water tiles in between, representing a river. Villages may be scattered over a broad plain, sometimes with superfluous empty grass or pavement to one side, or stretch diagonally across, or there may be outlying houses. Some are tiny, useless hamlets. Every place is different, just as it was with real settlements in our world that sprung out around a cathedral, a fjord or a mine. The visiting player must look on the map to navigate. In part this is simply because houses look almost exactly the same, even the ones that are supposed to be palaces or brothels, but the arrangement breaks the player's expectation that the geography will conform to the needs of gameplay. Instead the player must conform to the geography. Having to do that, he willy-nilly begins to take even these abstract settlements seriously, because challenge fosters belief. Compare this to the carefully prearranged streets of Baldur's Gate or Athkatla with exactly so much challenge and gold-containing barrels per area.

What is more, towns and villages in "Blade" don't have all requisite stores. In this game there exist three types of shops: chandler's, weaponseller's and herbalist's. Chandlers sell miscellaneous stuff like lanterns, torches, tinderboxes and food, though hunting in the wild is the better source of this last. Herbalists buy plants that the party's druids may find in the country, which is an important source of money, and sell some too in unlimited amounts, especially one cheap edible flower, the main means of healing in this game. Weaponsellers buy trophy weapons and furnish the party with arrows and crossbow bolts, and the combat system is so dull and broken that only missile weapons hit with any frequency. A party without characters equipped with bows and crossbows will die not from orc sabers but from the player's nervous breakdown. Now, there is much that is simply bad and awkward about all this commerce and equipage, but even in a well thought-out system access to all of the shops would be very useful to the party. Trophy weapons sell for a bundle, but they are heavy to carry around and reduce characters' action points in combat almost to nothing. A bunch of rare herbs plucked in the wild is idle money when there is no herbalist in sight. Chandlers also deal in some necessary equipment. Healers' shops can be essential for dealing with disease, and blacksmiths repair weapons. Today's player will expect all of these stores to be available more or less everywhere, a short walk away at most, and players of Baldur's Gate from 1998 can also count on a convenient, reasonable economy. It is simply the intelligent thing to do, and therefore obvious, and therefore ubiquitous. Not so in "Blade." Here small and even middle-sized settlements may have no weaponseller but two or three chandlers, the party may have to look for a herbalist in a neighboring town - or the one after that.

The availability of inns and taverns also varies, though only one hamlet, I believe, does not have an inn. As gameplay this is inconvenient, as a means of immersion - transporting. Selection is poor in small towns as well. All in all, economy is circumstantial. So are the options open to the party on any particular day in any place. Visits to taverns are a good illustration. Taverns are a useful source of rumors and sometimes outright needed to ask where in the town a particular contact lives, to avoid knocking on the door of every identical house, but the party gets to talk to the bartender only if he is not too busy serving other customers, which usually, but not always, requires coming in early, before the tavern fills up. It is easy to wander into taverns too crowded even to get a word in edgewise, and then the party will have to depart for an inn somewhere, rent a room and hope for better luck the next afternoon - or go knock on doors after all. This is annoying, but would be less so with a bit more variation, and finding the right house at last feels downright earned. Still, a general principle that makes itself felt here is that reward is not predictably commensurate with effort. This by itself is blasphemy to any modern game, but the fact is, nothing that is completely fair is true to life.